- Home

- Terri White

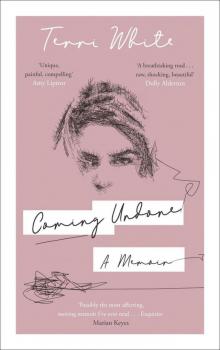

Coming Undone

Coming Undone Read online

Caution: this book contains references to sexual and other physical abuse, self-harm, addiction and suicidal ideation.

Some names and identifying characteristics have been changed to protect the privacy of the individuals involved.

First published in Great Britain in 2020

by Canongate Books Ltd, 14 High Street, Edinburgh EH1 1TE

This digital edition first published in 2020 by Canongate Books

canongate.co.uk

Copyright © Terri White, 2020

The right of Terri White to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on

request from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 78689 678 0

eISBN: 978 1 78689 679 7

For Margaret Noreen Carter.

And all the girls who fear they’re forever lost.

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Acknowledgements

CHAPTER 1

In my right hand is a transparent bag holding my clothes, basic toiletries and loose items of make-up. I step towards the automatic doors, which, sensing the movement, open with a whoosh: curtains announcing the matinee performance. I move forwards one small step, a second, and I’m through them, out on the street. I stand entirely still, close my eyes, breathe in, hold for two beats and then open my eyes wide and allow the world outside in.

Beeeeeeeeeep.

Beeeeeeeeeeeeeeepppppppp.

A yellow cab speeds past, horn blaring at a weaving cyclist who narrowly misses bouncing off its front bumper. A woman in a beige woollen skirt suit with a thin pink trim, short rigid curls and a face worn tight, bends down to scoop up her small white dog’s neatly laid shit with a tinted plastic bag, turned inside out and worn over her fingers and thumb. The bag might be scented, probably is, but I can’t isolate and identify that smell over the other smells writhing on top of each other, vying for attention. The odours of an average New York City street on an average spring day: garbage, coffee, noodles, piss, hotdogs, burnt sugar, beer, bagels. Sweet, bitter, soft, strong and sharp. The smells that become tastes when they travel up into your nose and down through your throat.

The grey, uneven patchwork pavement shakes, sizzles and bakes beneath my feet. I look from left to right, down at the concrete and up at the sky, or what’s visible of it between the towering buildings on this block. Wisps of white clouds scatter across an otherwise blemish-free blue sky; the sun blazes, burns bright. Tucked under my left arm are the flowers I was sent with love five days ago, by one of the handful of people who know the truth about where I’ve been. I had insisted on carrying them out with me, hand tight around the base of the basket, even though the flowers, the yellow and white daisies that had brought sunshine into the green ward, died yesterday. The heads are bowed and broken and brown, the soil flaky and cracked. I pull them closer. I flag a taxi with the hand holding the bag, my belongings held aloft and bared. I step down off the kerb, open the door, climb in the back and – just like that – I slide back into my life.

‘Avenue D and Third,’ I say to the driver.

I’m going back to my apartment in the East Village. My corner was once one of the very worst corners, the darkest corner of Manhattan’s drugs and crime-controlled no-go area. It’s now home to people like me, who push rental prices up and up, encouraging a Starbucks to open just two and a half blocks away.

Arriving home, I check my mailbox, which is overflowing, walk up the three flights of stairs and open the grey front door to my apartment, expecting resistance on the other side. Thirteen days ago, it was a wreck; more specifically the wreckage of a life in bits. The sink was stacked with dirty dishes, the worktops covered with take-out cartons and empty bottles. In the living room a carpet of crunched-up beer cans, wine bottles rolling on their sides, the prongs of plastic forks sticking in my foot every time I tiptoed to the bathroom, which was covered in damp towels, dirty clothes. In the bedroom, there were more discarded clothes, twisted stained sheets, fallen single shoes and bobby pins scattered like tiny traps across the bed and floor.

I feel both a rush of gratitude and a wave of shame crash into my chest as I walk into a transformed apartment. I don’t allow myself to think of my friend’s reaction when she came in, the door proving unyielding at first, after I gave her my keys to pick up some clothes. The message she will inevitably have shared, flying from Manhattan to Brooklyn and back again: did you all know about the mess? About how bad things were? Should we clean it? She can’t return to that, surely?

I picture her, picking up the discarded pills, one by one. The survivors that were last seen falling from my mouth, sticking underfoot and skidding into dark corners. The breadcrumb trail that didn’t lead me out of the woods, but was proof that I had been deep, deep in there, lost among the trees.

I drop my bag by the door, put my dead flowers down on the desk. A curled, crisp leaf lands by my feet. I look out of the window, hear sirens ringing out on the streets below. I become cold with fear, unable to move. Are they coming for me?

CHAPTER 2

Eight days earlier.

‘Hi! Um, I think there’s been a mistake,’ I say casually, with what I hope is an easy smile, high on the smallest glimmer of hope. There’s a noise, meant to pass as a light laugh, but which falls out of my throat somewhere between a hacking cough and a muffled squeal. The thick-bodied, heavy-eyed doctor stares an inch or so over my left shoulder and shakes his head. The forms I absolutely must sign are pushed towards me, curled up in his hand. He’s already filled his part in.

‘It’ll be more difficult for you if you refuse. This will all take longer,’ he says, gesturing around the room.

He should have made it home already, long before the sun outside turned orange and the sky beneath it went from blue to grey to black. His hair, brown and floppy – not unlike that of the boy who’d been my first frenzied obsession back in junior school – grazes the lids of his eyes as he blinks slowly, looks away, over my head, anywhere but at me. I try to make contact, convinced that once we lock eyes he’ll see the truth, as opposed to what presumably currently looks like manic terror, madness given voice. Can’t both be real? Both are real, to me, right now.

My fingers, freed after being strapped to the stretcher under blankets in the ambulance that conveyed me here, move up inside the sticky brown beehive pinned to my head. A habit which only a few – and certainly not this man, a stranger, yet one who already has such power – know to read as fear, my nerves prickling, rising, pressing against, needling my skin. I have a hospital bracelet on my left wrist, bearing a bleached-out picture of me. I know it’s me but I don’t recognise the face that stares back. The patterned hospital gown doesn’t quite reach my elbows but does reach past my knees; it’s tied at the back with three ties. The thin cotton socks from the previous hospital are s

till on my feet, which turn inwards as I stand, trying to think fast, not fast enough.

I make a small concession and take the forms and the pen, hands shaking, see the X where my signature is meant to go, the blank spot for my name. I don’t bring pen to paper. Instead I say, ‘Thanks! But I really want to talk to somebody. You know, now.’ I’m attempting a tricky balance between begging and assertiveness.

He looks at me finally, confused by the words I’ve just said.

‘Well,’ I say, in answer to the question he hasn’t asked yet, ‘about going home today. I just need to talk to someone quickly. It won’t take long. I’ve been in the other hospital for five days and want to arrange my discharge.’

I try to keep the panic out of my mouth and the edge out of my words. I’ve been planning this speech all the way over in the ambulance, not to mention for the last five and a half days and five nights I’ve been in another bed waiting for this one. The precise words and how they rise and fall and land in his ears. I can’t blow it now. He must see how sane I am. I try to ignore the mounting alarm, regulate every beat and breath as I realise that I only have seconds, not even minutes, to show him, convince him, make him understand who I am and how all of this is the most terrible of mistakes. I don’t belong here. Surely he can see that. Surely anyone could. I’m not entirely sure what a crazy person is supposed to look like, but I’m pretty sure it’s not this; it’s not me.

A small, bemused shake of his head and his stare disconnects, a light, my hope extinguished. ‘I’ve been waiting for you to arrive. I should have left already,’ he says. ‘There’s no one here to talk about it now. We can talk about it tomorrow, properly, but for now, you just need to sign. You can’t just go home.’

The spit of his impatience sticks to me, even as his gaze doesn’t leave the heavy air by my ear, where his eyes have moved once more. I think about the wife who pushed the golden band onto the second finger of his left hand, of their children, the calls to let him know that yes, they are still waiting for him and why hasn’t he left yet? The dinner bubbling in the oven, getting hard and losing flavour with each minute I delay him further. Around the table later, water glasses filled, ice melted, he’ll say how sorry he is, that the latest mad girl was admitted super late and he was the only one who could stay and she started asking to leave and he knows it’s only twelve hours until he has to be back there and he’s already said he’s sorry.

I start to read or, more specifically, push my eyes backwards and forwards, left and right across the page, slowly, hoping to buy even just a small fistful of time to think. I need it all to stop so I can just fucking think, press pause for a minute, make the world, this reality, stop. I sit on the bed and try to work it all out, so that when I press play again it will all be fixed and I won’t be scared.

But I am scared. Terrified. Because right now, none of this is going how I’d planned. I’d run this scenario in my head a hundred times or more and in each story, each sequence of events, I’m released back onto the city streets down below, relieved and, most importantly, free. Once I’m safely home, I put all of this down to a momentary silly slip, followed by an official overreaction, and within a few hours I’m eating alone in the bar of a restaurant, my third martini kicking against the back of my throat – empty and open.

The story in my brain sends the signal to my mouth and it floods with water, my tongue lapping against the wet waves. My mind wanders to smoky Irish whiskies warmed in the glass, a crisp, precise lager that dances and bubbles across my tongue, a wine that takes me to the Andalusian mountains and beyond. The shadow of my senses forms a solid shape, takes flight and moves just beyond my touch, my taste, my smell. The doctor sighs once more, harder and heavier this time, and all of the moisture is sucked out of my mouth.

I lick my lips, shake my head a little and focus, continuing to read, though none of the words and sentences are working their way through my eyes into my brain and becoming substance, becoming fact. They sit, instead, just inside my eyeballs, very still, intact but immovable, unknowable.

Though I don’t know what it says, I do know what it means. It means that my plan didn’t work. The one that was going to see me walk straight out of here, only minutes after walking straight in. An hour tops. We were meant to talk, laugh a little, shake hands, then off I’d go, plastic bag containing all my belongings swinging in one hand.

But now, the sun’s pretty much set on Thursday and I know in this moment that I’m now facing the weekend in here, at least. I can’t remember if he says this or if I just know it, instinctively, but it’s a fact. It could, in total, be days, weeks or even months: it definitely won’t be hours.

I look at his brown lace-up shoes, beige chinos, preppy blue starched shirt and black fleece with a high zip that must tickle his chin when he looks down at the floor, at his feet, which I imagine he does a lot. He isn’t like me. Or rather, I’m not like him. He doesn’t see who I am and certainly won’t in the window of time we have together tonight.

My stomach is in my socks – I don’t have shoes – as I submit, pressing the pen against the paper and pulling until my name, or a version of it, appears. I want to throw up but I smile, tighter now, and rest one hand on my belly in a futile attempt to stop it leaping and twisting with the knowledge and awareness of what I’ve just signed on for. I don’t know specifically what awaits me in the coming days or weeks, but I do know that this is the most dire, desperate situation I’ve ever found myself in. And I’ve been in a few. I’ve never felt more trapped; I’ve never been more trapped.

The reality of it travels through my body like urgent news down a wire – pins and needles sprinkle into my fingertips where they burst, tiny fireworks under my nails. Every cliché is coming alive in my body: the room spins; my head swims; I lose feeling in my ankles, my hands; everything out of my immediate eyesight is fizzy and fuzzy and distorted. The room goes cold, while heat floods my head. I can’t believe I’m still standing – I have to touch the desk to my left, just to make sure, in fact, that I am.

The part of me that I’ve only ever got a weak hold on pulls and tugs before breaking off and floating up to the ceiling; she squats in the darkness of the corner, staring at the top of both of our heads. It occurs to me for a second that I might have died and this might be death, the afterlife, or at least the life after. Every feeling in every inch of my body is alien, obscure, beyond my understanding. What other explanation is there?

I gather enough of my mind and my body to ask: ‘So how long will I need to be here?’ as I hand him back the pen and papers, now signed so he can leave. Which he starts to do immediately, shuffling past me as he says, ‘We don’t know. It’s impossible to say. You’ll be able to talk to someone about all of that soon.’ And with that he’s gone, out of the door. The door to the place that I’ve now agreed to call home, so the doctor can return to his.

It’s time to survive. I call her down from the ceiling and send her back into my body. This is how I’ll make it through: I’ll do what I’m told, what I must. What day is it? Thursday. OK. Can it really have been just Saturday that I was told in no uncertain terms that no, I couldn’t go home? It was. How many more days until I could go home? At least three. Probably more. I’ve survived almost six; I can take more. How can I get out? I need somebody to see, or at least agree I don’t belong here. I mean, I don’t belong here. I’m sure everyone says this. But I don’t, truly. I can’t; I just can’t. And if the doctor can’t see that, which, I’m guessing by his attitude he either can’t or won’t, I need to find the person who will. I will be the good little girl, barely causing an eyebrow to raise, while I tick off each day and wait, quietly. I’m not free, but the only way to become so again is to submit, willingly, with a closed throat.

Now it’s just me and the male nurse, who’s been standing silently watching our entire exchange. It’s not the first time he’s witnessed this, clearly. He first takes my obs – blood pressure, temperature and pulse rate – the three-times-a-day r

itual to measure my vital signs that I’ll come to know well. He then picks up and empties my plastic bag, the one that had transported my belongings from the hospital downtown. He sorts through them methodically, a sharpened pencil in one hand, itemising them, line by line: laptop, clothes, shoes, toiletries, make-up. Almost everything is a danger to me, because I’m officially a danger to me. I keep the make-up that doesn’t have sharp edges or is encased in glass: my lipstick, eyeliner, mascara. I keep a notebook and a pencil; he takes my laptop. I haven’t had my phone since the night this all started. I can’t have my shoes with laces, even though each lace – which couldn’t be more than twelve inches long – would only really make a noose suitable for a mouse.

He starts to fold up my clothes. ‘Wait,’ I say. ‘I need to take something to wear.’ As is becoming routine, he shakes his head: I can’t have my clothes yet. Not for the first day or two. He doesn’t say why, though the next day another patient tells me I ‘have to earn them’. No one from the hospital staff has said this is the case, but these words hit me. Earn my own clothes, the right not to have my backside hanging out. It feels like punishment. Like a marking of those newly mad or at least newly declared mad: the shuffling in socks and gaping gowns making you look as unkempt and loose, as wild, as lacking in civility and humanity as you feel. And with it comes a new feeling: shame. Like being painted with a thick brush from the ends of the hairs on your toes to the ends of the hair on your head.

The humiliation stirs a fist of anger within me. But I don’t say anything; I don’t put kindling against the flame and allow it to burn bigger. I just nod. Smile. My confiscated belongings are taken to a storage room at the end of the corridor, to sit in their plastic bag in a box, next to a row of other plastic bags in boxes. If I want anything from it, I’m to ask and they will supervise me using whatever it is I need. But they ask that people don’t do that unless it’s absolutely necessary. I wonder what necessary really means. And how many seconds you’d have to smash the mirror and take the thickest of the jagged shards to the thinnest part of your throat before anyone noticed or bothered to try and stop you.

Coming Undone

Coming Undone