- Home

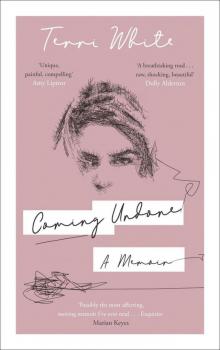

- Terri White

Coming Undone Page 4

Coming Undone Read online

Page 4

I need to start rebuilding myself, even if just the exterior. It’s time to paint my face, over features which have been left blank. I wipe foundation over my skin, becoming an empty page, erasing before I can colour myself into being again. I take the jet-black liquid eyeliner from the inner corners of my eye across and flick up at the sides. Blackest black mascara on each individual lash. Deep red lipstick stains my mouth into a violent permanent smile.

I pack the few items of clothes a friend has snatched for me from my apartment. My wardrobe is normally a carefully cultivated mishmash of second-hand dresses, shirts, skirts, T-shirts. Taken as separate pieces they look like the wardrobe of a deranged woman, but put together, it’s something approaching a look. A look that I could hide – exist safely – within. Grabbed at random, however, none of it worked. But it’s all I have with me to take to the next hospital: my wardrobe for the psych ward. My pink A-line dress; white shirt; a knee-skimming black dress that sticks to me in the bits that matter and those that don’t; a dogtooth mini skirt; an oversized T-shirt for my friend’s punk band; thick white tights; off-colour ankle socks; black tights with a ladder by the gusset; vintage lace-up brogues; a striped blue, white and red shirt with a dagger collar; navy blue cropped trousers; a thick yellow mini skirt.

I place my clothes, along with my make-up, a hairbrush and toiletries – moisturiser, hairspray, deodorant – and my laptop neatly in the big transparent plastic bag I’ve been allocated. The bags that you’re given when you leave or join an institution – a care home, a prison, a hospital. The sign that your belongings are, were, never really yours. They belong not just to whoever had given them to you, but to the world. The people who now have every right to see your knickers and your socks and your lipstick on display.

I wait. And wait. Visitors to surrounding beds come and go. The food trolley goes past en route to other beds. ‘None for me,’ I remind the porter with a smile, ‘I’m going to be out of here any minute!’ On the hour, every hour, I walk to the nurses’ station, still smiling while anxiously asking for an update. ‘It’s on its way,’ they say, on the hour, every hour. As each hour passes, I become more and more anxious. I can’t spend another night here in this ward, simply waiting.

It has taken several tear-fuelled conversations to my insurance company and the hospital administration team to sort the bed in the psych ward out for me. If it’s lost, I’ll be sent to the back of the queue. I feel beyond desperate just thinking about it.

I sit, stand, pace; I ask again. I don’t want to go to the bathroom in case they come and leave without me. The sun sinks a little lower. My bladder remains full. My fingers leave marks in the sides of the chair.

Eventually, several hours later, the paramedics appear: my rescuers. A middle-aged man and a young woman, swinging her high, tight ponytail, chewing gum. ‘We’ve had the worst day,’ they say to no one in particular as they pass the nurses’ station to collect me. They leave the gurney they were pushing in the corridor and come to the side of my bed.

‘Right,’ they say. ‘Time to get you on there.’

‘No thanks!’ I chirp, standing bolt-straight to attention as they invite me to get on the stretcher.

The female paramedic shakes her head. It’s not a request. ‘You have to,’ the man then chips in. ‘And we have to strap you in. It’s procedure.’

I look at the body-shaped stretcher, take a moment to steady myself. The thought of being strapped down, unable to move, takes the breath straight out of my body. They wait. Eventually, I climb up, covering my backside, as they ask me to cross my arms over my body, pull first a sheet then a blanket over me and strap me definitely not in, but down – tight, with black belts pulled across my body. They start to wheel me out and this is the exact moment the trembling starts at my ankles: an immediate, physical manifestation of the panic blossoming, opening wide, in my chest. I can’t move. I can’t breathe. Help me. Please. God. I don’t know who I’m looking at, for, but not for the first time that week, I look up. Up through the ceiling tiles, the electrical cables, the concrete, the tiles, the clouds, into the stratosphere, the sky beyond the sky we cannot see, no matter how hard we try.

As they continue wheeling me through the corridors to the elevators, the eyes of other patients and their family members fall on me, before bouncing swiftly away. Everyone can see the madness. The shame. They don’t want to be touched by it. There aren’t many other reasons to be tied down. I smile widely, red filling my cheeks. The skin in the corners of my mouth cracks, ever so slightly. My smile freezes still. They push me into the lift, talking over me; she casually texts; they laugh. As we get to the exit, my heart leaps. Through the doors, I can see the sunshine, the sky, the people hurrying, the cars speeding: New York, alive right there, just feet away.

I haven’t been outside, on concrete, felt the wind, tasted New York’s dirty air on my tongue, in almost a week. As the gurney pushes the external doors open with a bang of metal on metal, the air flies in and I instinctively open my mouth, gulping it down. If my hands had been free, I’d have been clutching at it, greedy with need. In the following seven or eight seconds it takes them to push me from the hospital exit to the ambulance doors, the wall of sun, wind, noise, clamour, chatter hits me square in the chest. Sirens collide with horns, meet screeching tires, melded with screams.

The paramedics continue to chat cheerily over my head, seemingly immune to the miracle happening all around us. Then they push me into the ambulance and slam the doors shut, shutting off my New York air supply. The ride uptown can’t take more than thirty minutes, but each one of them stretches out like an elastic hour. Not being able to move when you feel panicked is terrifying. Every bit of your body wants to thrash, pull against the ties and make a run for it. But you don’t. You lie very still, not moving a muscle, trying to forget you have muscles, a body under the belts, blanket, sheet. You breathe in and out, close your eyes, head on chest. The sounds rage outside but inside the only noise is the tap-tap-tap of the young ambulance tech texting on her phone. When we pull up to a stop and I open my eyes, she has a small smile playing on her face. She looks so free. In that moment, I hate her.

They wheel me into the hospital, up in the elevator, and then we’re buzzed in from behind locked double doors. As they push me past the room I’ll come to learn is for breakfast, lunch, dinner, supper, chair yoga, music therapy, group therapy, a row of heads turn around, their eyes landing on the new arrival. I keep looking straight ahead.

CHAPTER 6

My life began a long way from New York, in the village of Inkersall, just north of the Derbyshire town of Chesterfield. It was 1975 when my mum and dad first collided. My mum, running from her short life; my dad static, propping up the bar of the rough pub they met in. She was fifteen and living in a house teetering on a fault line. Perhaps the path to each other had already been forged, was simply waiting to be walked.

Her mother, my grandmother, loved to go out dancing and my grandfather loved to drink. He would be dead at fifty-six, their marriage burning and boiling up until the moment he died of a heart attack. Nana fingered the single earring, orphaned decades earlier by a blow to the head outside the working men’s club. She told the story of the night he broke her nose, blood spraying long and high up the wall of their neat front room. This was the world in which my mum lived, learned who she was and what she wanted.

Their love crackled bright and quick after a chance meeting in the pub and a wedding was quickly arranged for the day after her sixteenth birthday. My grandad, horrified and furious, made Mum an offer: a horse in exchange for her calling off the wedding. She loved riding more than pretty much anything; anything, it would seem, except my dad. The offer was swiftly rejected, the source of much claimed regret in decades to come.

In another quick act of perhaps easy-seeming rebellion, my brother was in her belly almost as quickly as they became hitched, entering the world a month before her seventeenth birthday. I joined them one year and 364 days later.<

br />

Much is disputed, but what isn’t is that their marriage was a disaster. He was jealous. He wouldn’t work. Their fights turned physical but only after Grandad died. When there were no other men around to protect Mum’s face, her body. Before long she was painted with bruises and waiting for the latest broken bone to fuse back together. There was a story she shared of the time she was pregnant, punched to the floor and kicked in her swollen belly. Another, of the Christmas she couldn’t see the turkey across the table; both eyes blackened and swollen completely shut, my newly widowed Nana closed-mouthed beside her, warned not to make it worse, because worse it could be. Still another, of the time he outlined, graphically, what would happen if she left him (as she eventually did), how he’d set fire to the house with us all inside.

Mum wasn’t his only target. He picked my brother off the ground by both ears and threw him against the wall. He punched me into the fireplace and sat on Mum as she screamed on the settee and I screamed for her in the ashes. That was the one, she says, that prompted her, finally, to take us and leave.

We escaped to Nana’s and he didn’t, in fact, set fire to us. The memories in the decade that follow are hazy, incomplete. There was, very quickly, a new, younger woman. Blonde with ‘CUT’ and dotted lines tattooed across both wrists, she was from one of our town’s toughest families. He drove a three-wheeled Reliant Robin, and the rare times we would visit him, we’d sit in the back, over the wheels, heads bouncing into the low ceiling.

They married quickly too, his reception in the working men’s club ending with linked arms and ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’.

The second White Family lived just six miles away, yet they only featured in snatches of my early life. There was a campsite holiday, our bags hastily packed after Dad knocked on the door unexpectedly after another extended absence. Upon arrival, my brother and I were sent to a small pouch in the back of the big family tent, which backed into a hedge. The rest of them slept together in the main section. At night, we sat with them in the communal area, drank Scrumpy out of brown bottles and listened to horror stories about murderers and ghosts and psychopaths before we skipped quickly back beneath the hedgerow. On the second night, while we were sleeping, the spending money Mum had given us to share for the week disappeared.

That holiday was a one-off, and for the most part, when it came to my dad it was waiting and wondering: where was he? When would we next see him? There was one afternoon in their house when we watched him kick his Alsatian dog with the steel toe of his boot. There were the days we spent cleaning his house – every room, every floor, every inch – exhausted by the time we were dropped home. They weren’t the memories you would cradle and keep safe.

I recall sitting on top of the sofa, my head stuck through the blinds, waiting, as he never arrived to take me to see Santa at the Co-op as promised. The hours ticked by. One of his – so I suppose by extension our – close relatives was getting married. It was my eleventh birthday. I remember turning up at the door of the fancy hotel in town, and being told that we couldn’t come in. That there had been a mistake. That we were not allowed into the ‘day do’. That there was no seat for us, no food for us. I tried to look around the big immovable man in the doorway, tried to see Dad so that he could come and save us. But I remember not being able to find him and us being sent away, back out into the street and being told to wait there for a few hours, until we were allowed in.

I was wearing a new dress, my perm tight and rigid. The temperature dropped as the sun dipped and my new, already much-loved Tammy Girl frock offered little warmth. As we sat on a bench by the roundabout in the shadow of the hotel, the sky turned black and I started to cry. My defiantly dry-faced brother – who was already my eternal protector at just thirteen – comforted me. After more time passed and we still weren’t allowed inside, I remember walking to a phone box and reversing the charges to ring Mum and that Dad later claimed it had been a ‘mix-up’. My cheeks burned at the thought of him sitting inside – scraping his plate clean, while his children were exiled – in the belief that he didn’t really want us, never had.

Until then, I’d always fantasised about being a daddy’s girl. It was a dream that I tangled in between my fingers and tried to make real in my fists. It had first bloomed in my brain at around six or seven years old: the age I first understood that my life and that of kids around me didn’t line up. Through the smudged lenses of my thick NHS glasses, I hungrily watched my friends with their fathers, devoured their casual interactions. The light way they laughed, how their fingers entwined easily, the gentle care of a jacket being zipped all the way up to the chin. It always amazed me to see the dads waiting nervously as we clambered off the bus from the school trip or when they poked their heads gingerly around the door as we wrapped up at Brownies. It all just served to make me ask: I had a dad out there, so why wasn’t I good enough to be his girl?

But now, as disappointments piled up and my desperation to be a daughter waned, I resigned myself to being without a dad. Just as well: contact petered out altogether before I began secondary school. His position appeared to be that we knew where he was if we wanted to see him. We did, and I for one didn’t in the face of his ambivalence. Until I turned seventeen. Then I became suffocated by the need to find out who this man was. To find out who I really was. It was teatime on Boxing Day when I knocked on his door.

‘Hello, duck,’ he said, seemingly only moderately surprised, vaguely pleased to see me. I went in, had a cup of tea, we made polite conversation, I left. Hopes of a restorative process, leading to a real father–daughter relationship proved, to me, overly optimistic, impossible. In the preceding years I’d watched Surprise Surprise avidly, imagining our reunion: the tears, the joy, the feeling of coming home. But looking into his eyes – so much like mine – I felt no rush of love, no sense that I was inextricably his. I was sure he felt the same. We kept up sporadic visits nonetheless. His wife would take us walking through graveyards at midnight, on the hunt for ghosts. Other than that, we sat in uncomfortable silence in front of the TV as horse racing and the bloated voices of those who narrated it roared out.

It finally ended not unlike it began. I was nineteen and leaving for a summer abroad. It was also my birthday. He was coming round to ‘say goodbye’ after he’d turned me away from his door earlier in the day, when I’d arrived unexpectedly with a Father’s Day gift. ‘I’ll be there by seven p.m.,’ he promised, buying time, time he’d pocket, never intending to use.

I sat by the window and waited, each set of passing headlights a fresh disappointment. As I started to cry, I remembered the almost identical scene when I’d been waiting to see Santa. When I’d sat and waited, refused to come out of the window. When I’d allowed myself to be strung up in misery. He hadn’t come then, and he wasn’t going to come now. He would never come, never realise his responsibilities. At four a.m., I closed the blinds and wiped my face. As I walked up the stairs I thought: the question really was not where was he but who was he? I didn’t know him. He wasn’t a dad. At least, he wasn’t my dad.

Some five or so years later, a brief rapprochement. My phone rang. It was my brother, telling me that Dad was in hospital. His wife had recently died and he’d driven out into the dark countryside lanes and had an accident. He was in intensive care and we were advised to see him while there was time. I took the train and arrived at his bedside, thick, tied tubes lodged in his throat, mouth, machines beep-beeping, pulsating. I felt like a charlatan at his bedside.

Against the odds, he survived; he recovered. Once he did, I recall him promising to be there, to be present, saying how much he missed us, how much he missed me. I felt nothing then, and nothing again when, once again, he disappeared from my life – leaving me with no consoling memory of a goodbye.

CHAPTER 7

Into this gap, the father-shaped hole in my life, walked other men, almost immediately. I never had the chance to hope they would be better men, better fathers than mine had been – it was clear fr

om the start that some were, in fact, much worse. The first that was worse arrived within a year or two of the day we fled Dad.

There was a morning. A morning when I looked at him from where I sat curled up on the sofa. This morning, he was solid. Just yellow hair, white skin, hard bone. Just blood. I knew that if I nicked his thumb with a butter knife, red would run into the blond hair that curled around his wrist, making a crunchy matted knot that tasted like metal as you sucked. It lay heavy and thick on my tongue.

He winked now, safe in his security. ‘So,’ he said. ‘We played wrestling last night. Right?’ The first bit was for her; the second was for me.

I giggled and bowed my head. ‘Yes.’

She nodded as the acrid smoke from the frying pan snaked and settled into the twists and turns of her perm. We glanced, co-conspirators now. The familiar shiver and nauseous bloom in my tummy. I laid my arm across to stop it spreading and gripped my second rib, holding myself in place.

Her make-up was smeared and her smell sour, but last night she stood in thick choking clouds of Elnett and perfume. Smoothing down her leather skirt and tilting her head, she’d put the finishing touches to the woman in the small mirror perched on the windowsill over the sink. I could tell she was pleased with what, who she saw. I practised arching my back and raising my cheekbones skyward: first one and then the other.

There was a night. A night that she moved down the hall, carried away on her familiar sweet smell. I clutched at her with sticky fingertips as she glanced my way, irritated by the tiny person she recognised but didn’t see.

‘What?’

Panic swelled my tongue dormant. ‘It’ll hap-p-pen,’ I managed to stutter, an increasingly frequent occurrence by then, soon to be joined by wetting the bed. ‘If you … go.’

Her heels hit the uneven steps down the front path as she went. I watched her grow smaller in the frosted glass, until she disappeared entirely. Then there was just me and him under the darkening sky.

Coming Undone

Coming Undone